In the late ’80s, New Castle County authorities investigating the brutal killing of two women would soon learn that a serial killer, dubbed “The Route 40 Killer”, was hunting young women along Route 40.

On November 29, 1987, The first victim, 23-year-old Shirley Anna Ellis, left Wilmington Hospital around 6 PM. Ellis thinking she was catching a lift on her way home on Route 40 never made it home. Two teenagers would later find her body by the roadside. At the scene, the police found the victim wearing a pair of aqua blue pants. There was black duct tape in her hair. Ellis’ injuries were extensive, including ligature strangulation marks around her neck, numerous skull lacerations consistent with being struck by a hammer, wrist injuries suggestive of binding and pattern bruising to the left breast and nipple. The Medical Examiner determined that Ellis’ death was caused by strangulation and blunt force head trauma. Court records indicate that Ellis was known by police to be a prostitute.

On June 29, 1988, the nude body of the second victim was 31-year-old, Catherine A. DiMauro, was discovered at a construction site. Numerous blue fibers were collected from her body and two red fibers were removed from her face. In addition, a piece of duct tape was removed from DiMauro’s hair. The injuries to DiMauro, also a known prostitute according to court records, were very similar to those suffered by Ellis. Moreover, the Medical Examiner determined that DiMauro’s death was caused by multiple blunt force injuries and strangulation the identical causes of Ellis’ death.

As a consequence of the Ellis and DiMauro murders, in July 1988 the police put together a task force of over 60 people, including the FBI’s profiling unit. The group determined that a serial killer was operating in close proximity to Route 40.

In an attempt to identify the killer the task force began a decoy operation along a highway corridor which the victims were known to frequent. As part of the operation, female police officers wearing hidden microphones were dressed as prostitutes and engaged in conversations with men who stopped for them. The officers were not permitted to enter the vehicles of these men.

On August 22, 1988, another prostitute according to court records, Margaret Finner, was reported missing. She was last seen entering a blue van, which was described as having no side window and rounded headlights. This information was incorporated by police into their investigation and decoy operation.

On September 14, 1988, Officer Renee (Lano) Thasher was working as a decoy along Route 40 when she observed a blue van cruise past her seven times. Officer Lano called in the tag number of the van and learned that it was registered to a white male, 31-year-old Stephen Brian Pennell. After Lano moved to a darker area of Route 40, the blue van stopped for her. The driver motioned for Lano to enter the van. Lano approached but did not enter the van. She spoke with Pennell who appeared nervous, hardly looking her in the eyes, but he still attempted to convince her to enter the car. During the conversation, Lano became suspicious of Pennell and noticed that the interior of his van was covered with blue carpeting. Aware that blue fibers were found covering DiMauro’s body, Lano surreptitiously removed some blue fibers from the door jamb of Pennell’s van.

On September 20, 1988, the body of a young woman was discovered on rocks by the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal. The body was identified as Michelle Gordon, also known to police as a prostitute according to court records. The Medical Examiner concluded that Gordon was the victim of a homicide, but because her body had been submerged in water, no determination could be made as to the cause of death. During Gordon’s autopsy, officials determined that she had been drugged with cocaine, which had caused her heart to stop before the torture had begun. Injuries inflicted on Gordon’s body were very similar to those found on both Ellis and DiMauro.

On September 23rd, 26-year-old Kathleen Anne Meyer, of Brookmont Farms, disappeared. A police officer saw her get into a blue Ford on Route 40, at 9:30 PM. He was able to write down the license plate number, which turned out to belong to Pennell’s vehicle. Her body was never found.

The police began surveillance of the defendant. Pennell was observed repeatedly cruising the same area of the highway corridor that was the site of the decoy. On September 30, 1988, the police stopped Pennell for a traffic offense. A search of his van uncovered a bloodstain. Blue fibers and swatches of red cloth were taken from the van. Delaware public prosecutor Charles Oberly approved a police search warrant of the panel van. Search warrants were subsequently issued for Pennell’s trailer, shed, vehicles, and his person. Pursuant to these warrants, police seized a buck knife which was in the defendant’s pocket, eight pairs of pliers, a bag of unused flexicuffs, and two rolls of duct tape.

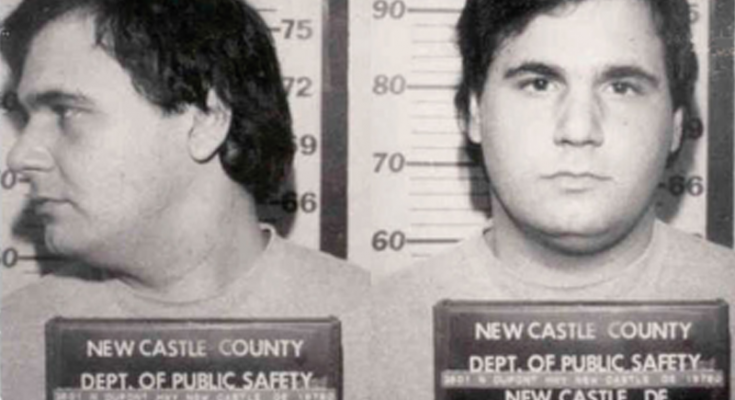

Pennell, an electrician, married, and father of two, with no criminal record, was taken into custody on November 29, 1988, a year after he murdered the first victim. He was charged with first-degree murder for the deaths of Shirley Ellis, Catherine DiMauro, and Michelle Gordon. He invoked his right to remain silent.

On September 26, 1989, Pennell’s murder trial began. As the trial started, a panel of defense attorneys tried to have the blue fiber evidence tossed. They claimed that the initial fiber taken by Officer Tashner was obtained illegally because it was taken from his vehicle. Judge Richard Gebelein dismissed these allegations, saying that the carpet was visible to Tashner’s eyes as soon as she opened the vehicle, so evidence from these fibers would be allowed. Once the fibers were examined, it was shown that they had DNA residues belonging to the victims. It was the first trial in the United States that used DNA evidence as absolute legal evidence. Judge Gebelein had to set a legal precedent and listen to the opinions of experts and scientists, who helped verify the DNA evidence.

As part of its case in chief, regarding the “serial” aspect of the murders, the State was permitted to introduce evidence of the disappearance of a woman named Margaret Finner. The jury, however, did not know Finner’s name or that she was eventually found murdered. Agent John Douglas, Director of the F.B.I.’s Behavioral Sciences Unit, testified as an expert in the area of serial murders. After reviewing the deaths of Ellis, DiMauro, and Gordon, he opined that they were all committed by the same person.

After over two months of trial, the jury deliberated for eight days, setting a record for the longest hearing in Delaware legal history. On November 23, 1989, the jury reached a decision and convicted Pennell of murdering DiMauro and Ellis, but the jury was unable to reach a verdict on Gordon’s murder. The jury recommended two life sentences, opting not to recommend the death penalty.

Pennell’s lawyer appealed the court’s decision claiming the trial court abused its discretion in denying his motion for a mistrial based upon remarks made by the prosecutor in her final summation to the jury; the trial court abused its discretion by admitting evidence concerning the disappearance of a prostitute in the area where Pennell’s victims were allegedly abducted; the search of Pennell’s van, and the seizure of blue fibers therefrom, violated the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution and Article I, Section 6 of the Delaware Constitution regarding unreasonable searches and seizures; the trial court abused its discretion in allowing an F.B.I. Agent to testify as an expert on serial murders; and there was insufficient evidence to support the conviction for first-degree murder for the death of one of the victims, Shirley Ellis. The appeals court found no merit to Pennell’s claims and affirm his convictions.

After his appeal was denied, new evidence linking Gordon and Meyer’s deaths to Parnell was introduced. He was then indicted on two separate charges of Murder in the First Degree. At this point, Pennell dismissed his attorney and ask the court to allow him to defend himself.

Acting as his own attorney, Pennell would subsequently enter pleas of no contest on the new murder charges and informed the court that he wanted to receive the death penalty. On October 31, 1991, following a penalty hearing, the Superior Court sentenced Pennell to death by lethal injection for each crime. His execution date was set for March 14, 1992. He did not file a direct appeal.

An automatic appeal was docketed with this Court on November 1, 1991, pursuant to Delaware law. The review of the imposition of the death sentences by the Superior Court, following each of Pennell’s convictions of Murder in the First Degree, concluded that the judgments and sentences of the Superior Court should be affirmed.

On November 8, 1991, Pennell informed the Clerk of this Court, in a hand-written letter dated November 3, 1991, “of his decision that no action will be started by him against the conviction or sentencing.” Pennell also expressed his “wish to have the automatic review of the death sentence …* The letter also stated that Pennell would “respectfully object to any counsel other than himself being appointed” to represent him in this Court.

On November 14, 1991, Pennell, acting as his own attorney, filed a handwritten document with the court, titled “Notice to Dismiss Appeal and Affirm Judgment.” In that document, Pennell requested this Court to affirm the death sentences that had been imposed by the Superior Court “so that the proposed sentence can be carried out without delay.” On November 25, 1991, the record of the proceedings in the Superior Court was filed with this Court. On December 2, 1991, this Court concluded that, in the interest of justice, this matter should be remanded to the Superior Court for an evidentiary hearing on Pennell’s applications: to represent himself on appeal, to dismiss the appeal, and to affirm the judgments of the Superior Court, which had resulted in the imposition of both death sentences.

On December 19, 1991, the Superior Court conducted an evidentiary hearing. The Superior Court found that Pennell’s decision to proceed as his own attorney on appeal was made knowingly and voluntarily, with a full understanding of the dangers of pursuing self-representation and the disadvantages he may encounter as a result of not having an attorney representing him on appeal. The Superior Court also found that Pennell understood the limited nature of this Court’s proportionality review of a sentence of death. The Superior Court further found that Pennell realized that if his motion to affirm was granted, it would result in his execution. On January 7, 1992, the Superior Court approved and adopted the lower court’s findings, clearing the way for Pennell’s execution.

Despite a last-minute appeal by Pennell’s wife, Vera Catherine Pennell, Delaware’s only known serial killer was executed On March 14, 1992, at 9:49 PM, by lethal injection, becoming the first person executed in Delaware in 46 years, and the 165th person to be executed in the United States since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976. He had no last words.

Prior to his execution Pennell was asked to disclose where he had hidden Meyer’s body, however, he would not answer that question.