Scientists at ChristianaCare’s Gene Editing Institute have received a $1 million grant from the Lisa Dean Moseley Foundation to develop a novel gene therapy for inherited blood disorders including sickle cell disease, offering hope to nearly 100,000 Americans suffering from the disease who are disproportionately African American.

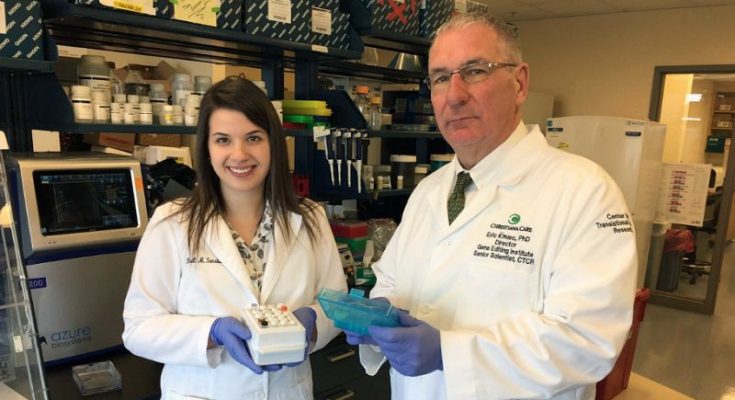

Building on previous work that showed how gene editing efficiencies vary from person to person, Director Eric Kmiec, Ph.D., and his research team are exploring the genetic reasons governing who might benefit from this therapy and who might not, a question that lies at the very underpinnings of personalized medicine.

“Our work has set the foundation for understanding the importance of genetic diversity in such treatments,” Dr. Kmiec said. “We anticipate that our findings will have broad impact on biomedical research and genetic medicine.”

Dr. Kmiec’s team at the Gene Editing Institute has prioritized work in diseases that impact minority communities.

“Development of successful treatments for diseases among minority communities has lagged far behind those for diseases that affect the general American population,” Dr. Kmiec said. “This grant will help us reverse this trend and fulfill our central mission to translate bench-top research to clinical applications for the medically underserved.”

Designing gene editing tools to tackle sickle cell disease

Using CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) technology developed in his lab, Dr. Kmiec and his research team will design genetic editing tools to reverse the single base mutation in the hemoglobin gene that causes sickle cell disease. Through their experiments, the team hopes to identify the CRISPR molecule that works most effectively on a large and genetically diverse group of patients.

“It is entirely feasible that CRISPR-directed gene editing could become a widely used treatment for sickle cell disease and other hemoglobinopathies, such as hemophilia and thalassemia,” Dr. Kmiec said.

But building CRISPR-directed gene editing strategies to treat these disorders presents unique challenges.

“It is largely believed that genetic diversity among individuals changes the way human cells respond to genetic engineering,” Dr. Kmiec said. “Thus, a more robust approach particularly with the goal of developing a new therapy for sickle cell disease must take into account human variations.”

Researchers at the Gene Editing Institute discovered such variations by carrying out experiments in human stem cells, called CD34 positive progenitor cells, using a CRISPR strategy designed for correcting the sickle cell mutation that affects the hemoglobin molecule in red blood cells that delivers oxygen throughout the body.

Each patient sample the Gene Editing Institute tested generated a different level of precise or error-prone gene editing. The grant will allow researchers to expand on this work and test many more patient samples.

The team will work in partnership with the Coriell Medical Institute in Camden, New Jersey to obtain progenitor stem cells for study from large genetically diverse populations of sickle cell and healthy patients, both African American and Caucasian.

Factoring in diverse genetic backgrounds in sickle cell disease

Using the Gene Editing Institute’s patented cell-free extract CRISPR gene editing on a chip system, the team will make independent assessments of both genetic diversity (by using different patient samples) and the impact of potential, therapeutically relevant target cell types to create an accurate profile of gene editing applicability. The next step will be to measure the efficiency and accuracy of chromosomal gene repair of the sickle cell mutations in potential target stem cells.

“The outcome of our work will be a rationally designed, maximally effective and validated toolbox that can have broad use in the development of CRISPR-directed gene editing as a therapeutic approach for sickle cell and other blood-borne diseases,” said Brett Sansbury, Ph.D., the Gene Editing Institute’s Discovery Group leader and project lead investigator on the grant.

Sickle cell anemia is one of the most common, hereditary diseases caused by a single gene and is an emerging global health burden. The disease is more common among certain ethnic groups including African Americans, among whom 1 in 12 carries a sickle cell gene.

Research under the grant will also support The Gene Editing Institute’s use of its CRISPR in a Box™ educational toolkit to engage high school students in underserved communities to participate in the fight against sickle cell disease.

Source: Christiana Care